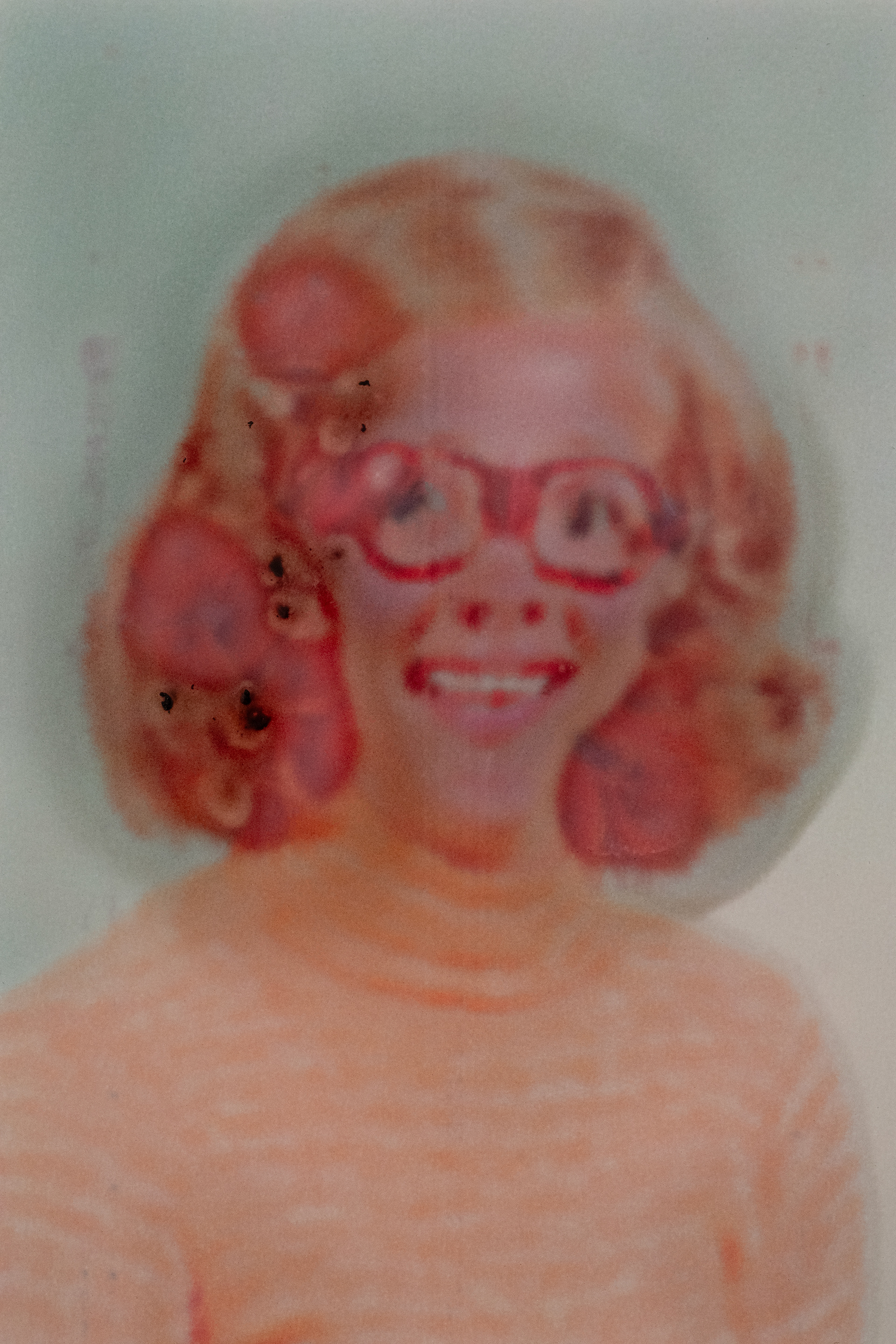

" Aura/Halo" Photo album edition, 1/2 inkjet prints on found photo album (2025)

This photography series explores my reflections on individual memories and their loss.

In the summer of 2013, my mother had something to discuss with me. She explained that my father had started asking the same questions over and over again. When my mother mentioned this to a friend who had experience as a caregiver, her friend encouraged her to take my father to the hospital immediately for testing. Subsequently, she took my father to the hospital, where he underwent several days of testing that fall and was diagnosed with early Alzheimer's disease. My father's story was documented in detail in my series of documentary photographs titled “Dad Went on A Journey.”

Needless to say, dementia is a disease associated with the decay of memory. Over time, various memories in my father's mind faded away one after another. While photographing him, I became fascinated by the mysterious phenomenon of human memory and its loss. For no apparent reason, I started purchasing bundles of old photographs, glass plate negatives, and radiographs from eBay and thrift stores in New York.

I have a large number of photographs in front of me, and I don’t know who took them or who is in them. Most of the moments captured in these photos likely represent the happy days of an ordinary family that once lived in the United States. Perhaps these images reminded their previous owners of joyful times in the past.As I looked at these piles of old photographs, I realized a simple truth: all of these images, now stacked in large quantities before me, have already served their purpose as memory storage devices. Most were taken only 50 or 60 years ago. This suggests that photographs, as “archives,” often lose their detailed meaning after just half a century, leaving behind only vague traces of a place or time. The information supposedly captured in the photographic medium has a much shorter lifespan than the medium itself, which strikes me as quite strange.

One day, as I was printing images of my father and mother, I accidentally set the print paper backwards. The inkjet printer made a mechanical noise as it sprayed ink onto the reverse side of the paper, which wasn’t meant to be printed. When the print was finished, I saw a blurred, blotchy, distorted image of my mother. This bizarre and somewhat frightening image, created by chance, left a strong impression on me. The ink on the back of the paper, which shouldn’t have been printed, slowly changed and shifted, never fully fixed. To me, this evolving image resembled a memory gradually deteriorating in an individual’s mind.

I chose to bring these images, and the emotions they carry, back to life as “photographs.” I printed portraits I’d collected over the years onto the backs of regular printing paper, omitting any details about the photographer or the person captured. These portraits, their outlines and forms fading, lose the clarity and context they once held, reappearing before us like ghosts.

The emotions evoked by the image were not uplifting. A thick sense of vague anxiety and dread permeated the images, as if one had witnessed something that should not be seen. This unease and fear felt instinctive and intuitive. I realized it likely stemmed from how the image triggered deep human instincts—the fear and anxiety of being forgotten and lost.The images of these unknown people return to the present as symbols of lost memories. We may encounter them briefly in the world of Instagram and the Internet, but their original forms have already lost their clear outlines, dissolving in the vast sea of memories. Like them, we too will lose our own outlines in less than 50 years. In fact, it may happen even sooner, as we have already lost the culture of preserving our images in print.